People, don't you understand

The child needs a helping hand

Or he'll grow to be an angry young man some day

Take a look at you and me

Are we too blind to see?

Do we simply turn our heads

And look the other way

~Elvis Presley, “In the Ghetto”

Supergrit

As a child, my mother knew where the rat poison was, “just in case” she wrote in her unpublished memoir. Just in case her life got a notch worse. It was already bad. She was a dirt poor hillbilly born with one arm to an uneducated alcoholic coal miner and his uneducated disciplinarian wife. The wife reckoned that her first-born’s birth defect was God’s punishment for her own sins. From the sound of it, that belief led to some of what we would nowadays call child abuse.

By “dirt poor,” I mean they not only didn’t have running water, they didn’t have their own water well for many years. Mom and her siblings, of which there were 5 born alive, got one bath each week. The six children used the same bathwater, with Mom as the oldest going last. She said they alternated between two dinner menus. One was beans and cornbread, and the other centered on whatever cheap meat they could buy or kill.

Her life did get worse, but not bad enough for the rat poison. As a married teenager, she became the mother of a severely physically and mentally disabled son. Very soon thereafter, she divorced. Meanwhile, even though education beyond high school was frowned upon in her family, she earned a college degree while keeping her doomed boy alive. Knowing my mother, she would have dutifully loved and cared for him until he died at age seven.

She kept going. She got a job in a biology lab and married a professorial descendent of Puritans — my father. They had two children, one of whom (my sister) turned out OK. My mother’s supergrit was accompanied, predictably, by life-long hyper-vigilance and lack of self-care. As is often the case, I think, those habits fed into depression and anxiety. So she always kept an eye on the “rat poison.”

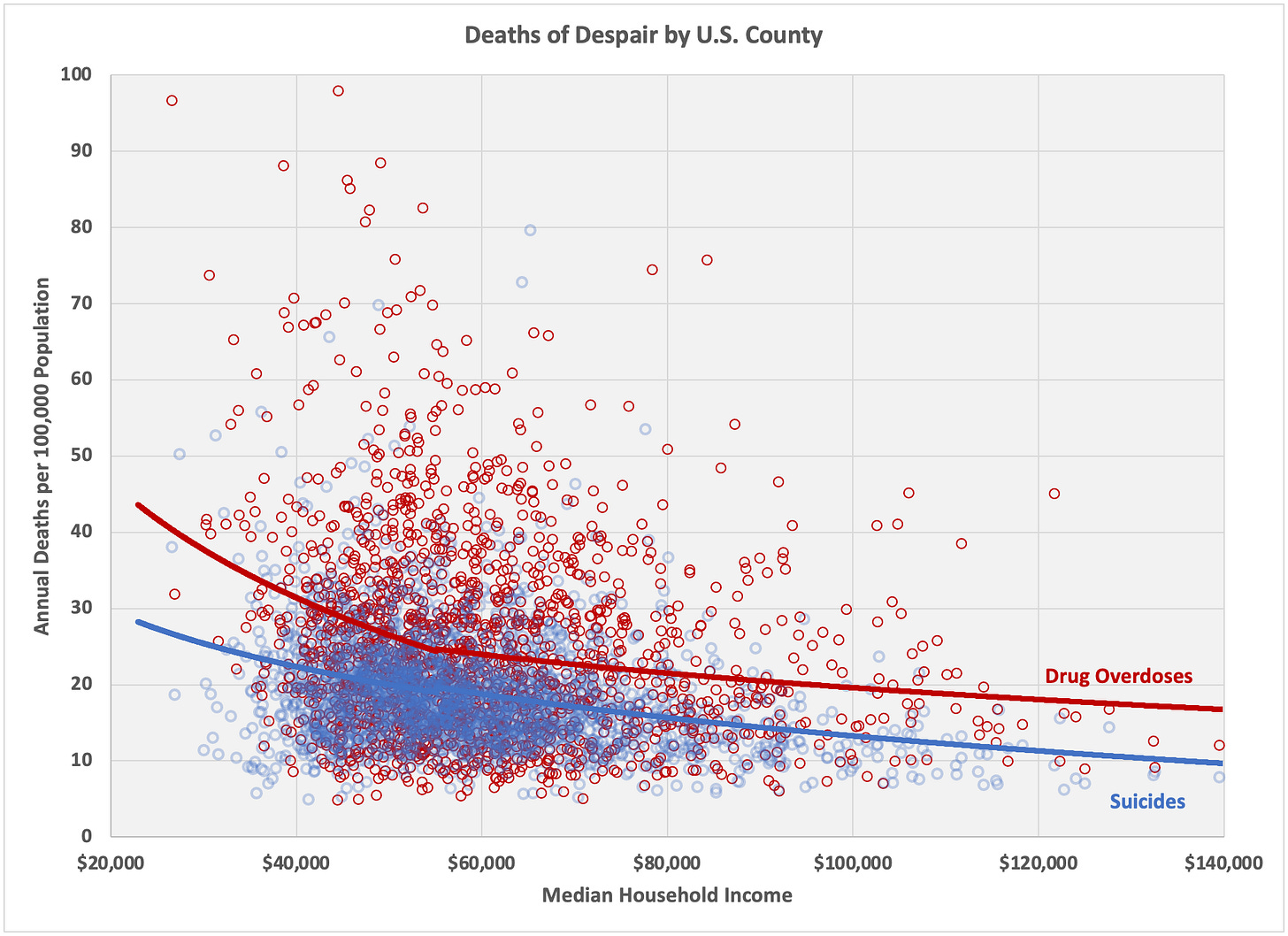

Mom told me the only reason she didn’t get into drugs when she was a teenager is she didn’t have access to them. That would be untrue now. The county she grew up in — Bell County, Kentucky — has a drug death rate of 40 per 100,000.

Although personal to me, this is just one story — hardly enough to justify changes in national policy. But if there were a top-down, systems-thinking explanation that aligned with this story and all the others like it, we might begin to really understand the correlation between household income and deaths of despair. Of course I think there is a top-down explanation and here it is…

Economics is Human Nature

We humans have taken over the planet with a strategy unique in the animal kingdom: individuals are highly specialized. We differentiate and cooperate. One could argue that other animals – pack animals, hive insects, other apes – specialize and work together. But in this regard, we are extreme.

Look at us. We are fangless, clawless, slow, weak, and furless. How did we survive as a species?

By specializing and working together. No single person’s expertise is enough to support a society. Societies are built on networks of specialized individuals. We each do a specific thing, leaving other necessary specifics to other people. In other words, we trade expertise amongst ourselves. We specialize and trade.

“Specialize-and-trade” is my favorite definition for economics. It captures the fact that economics is deeply human.

Capitalism is Human Nature

To deliver expertise, a person needs tools. A tool might be a piece of equipment like a backhoe or a computer. Or it could be a structure like a barn or a warehouse. Or just acreage, as in agriculture. These are examples of physical capital. We also use “human capital.” Human capital is the expertise accumulated through education, training, and experience.

Building each tool requires expertise, too. Tool building requires its own set of tools. Etcetera. We need the expertise of others to develop and deliver our own. As a rule, we need the expertise of others before we ourselves can deliver any appreciable value.

Suppose a person needs a tractor to grow spinach. She can’t afford to buy a tractor, but let’s say she wants to borrow one. That’s a good deal if she can find it, but if the only tractor owner in the area is not a close friend, she will have to rent. Why rent? Because the tractor’s owner would be taking a risk. He might not get his tractor back for some reason. And if he does get it back, it will have depreciated in value from use. To compensate the owner for risk and depreciation, the borrower pays rent. To summarize, the owner of capital exchanges risk for money.

That is called capitalism. The capital could also be human capital or financial capital. The point is that we trade value across time, not just across space. That is what capitalism does. There is no way we could have gotten this far without capitalism. And there is no way forward without it. Capitalism is part of being human.

Is Inequity Human Nature, Too?

Capitalism is part of human nature…but not the whole of it. We also have a social nature. We impose social norms on one another through laws, contracts, public service announcements, “cancel culture,” and Aunt Betty’s tsk-tsking or warm hugs depending on the situation. In this way, with varying degrees of success, we try to keep things fair.

Even in a hypothetical capitalist economy untainted by excessive intergenerational wealth accumulation, systemic racism, and the like, the rich would get richer. That’s what happens when the capitalist rents out physical, financial, or human capital. It naturally leads to income inequality — so far, so good. The problem is that income inequality, left unchecked, leads to inequity.

To answer the question, equity (driven by our social nature) and inequity (an unintended consequence of specialization) are competing outcomes of human nature. Inequity feeds on itself, trending worse, whereas efforts to keep things equitable do not. Over time, then, inequity tends to win out.

Note, however, that this dour conclusion hinges on the “left unchecked” phrase. We don’t have to leave the links between income inequality and inequity unchecked!

Capitalism and Despair

Another facet of human nature is a visceral need for each of us to be seen and valued for who we are. Who we are is demonstrated by how we participate in society’s boiling human stew of value delivery while trying to stand on each others’ shoulders. We call it “economics,” but it is more deeply personal than the word suggests.

Imagine how it would feel to be consistently and systematically stymied in your efforts to reach your full potential and add your best value. The word despair comes to mind. That’s what inequity does.

Next up: Why does inequity feed on itself? A visual explanation.