Note: This is Part 1 of 3 on a journey to six principles for economic resilience.

What, Exactly, is Resilience?

Resilience is a hot topic. I hear about it in the context of our electricity grid. Cyber resilience is a growing industry. The White House issued a brief on supply chain resilience in late 2023. The National Alliance on Mental Illness outlines strategies for mental health resilience. And, of course, there is concern about society’s resilience in the face of climate change.

People who study resilience inevitably try to clarify the meaning of the word by distinguishing it from reliability. Me, too. Resilience is low sensitivity to unforeseen disturbances. Say a tree falls on a family’s car which they need to escape a deadly storm. Resilience in that case might involve a creative solution like hot-wiring the neighbors’ (abandoned) second car. Also, maybe next time a major storm threatens, the family moves their own car out from under all trees.

Reliability is indifference to ordinary disturbances we are confident will happen without knowing exactly when — a car battery dies, say. To be reliable, we would need an alternative plan for getting to work and/or preemptively replace the battery before it dies.

Resilience and reliability address different kinds of risk. A useful way to think about risk is probability x consequence. High risk could be due to either a high-probability threat or a big consequence if and when the threat materializes. Resilience deals with low-probability, high-consequence disturbances; reliability deals with relatively high-probability, relatively low-consequence disturbances. (If the threat is high-probability and high-consequence, it is dangerous, not just risky, a different conversation.) For example, a hospital’s resilience in response to pandemics is different than its reliability in the face of the cold and flu season.

Furthermore, resilience definitions usually include learning of some sort: “organizational learning,” “bounce-forward,” “continuous improvement,” “personal growth,” etc.

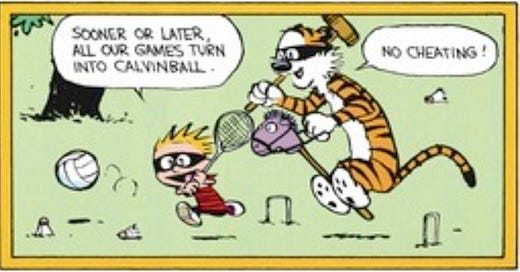

Resilience is tricky because it asks us to be, if not entirely indifferent, unlikely to collapse in response to high-consequence disturbances we did not see coming. Furthermore, after the immediate recovery, resilience implies that we learn and improve. That is pretty hard to do if we over-focus on optimization. Optimization is a strategy for reliability. But as Brian Klaas writes in “The Perils of Moneyballying Everything,” optimization is a losing strategy if the game actually being played is Calvinball.

The strategy for resilience? Stewardship.

(Coincidentally, Brian published a post this very morning asserting that optimization is a “trap,” and resilience is a “smarter, sturdier goal.”)

OK, So What is Stewardship?

Stewardship is what we do; resilience is the result. Resilience emerges from stewardship of a key underlying resource. This is a resource that, when healthy, offers multiple interacting longer-term shared benefits. To steward a resource is to tend to its future health and therefore future benefits for all who rely on it.

The Grid, an Example of Over-Optimization

For example, our electricity grid’s resilience, especially as we add more renewable energy sources, relies on energy storage. By default, energy is generally stored in the form of fossil fuels kept on hand, ready to fuel back-up generators at utility and retail scales. And we have some utility-scale energy storage technologies arguably more suited to compensating for the vagaries of renewable energy. One example is pumped hydro, which makes use of water pumped, using excess power when it’s available, uphill to the reservoirs behind hydroelectric dams. The problem with that one is it depends on rivers and dams. Meanwhile, grid operators put a lot of work and technology into monitoring, moment by moment, electricity supply and demand and matching them exactly — in a word, optimizing.

Our grid is optimized for fossil fuel-based power production, so as we transition to renewable sources (which are less reliable because of weather and sunsets), we are running into problems that manifest as bureaucratic resistance to progress. Besides enabling the incorporation of renewable energy sources onto the grid, decentralized energy storage minimizes the reach of local disruptions to the grid at large, thereby contributing to systemic resilience. Decentralized and plentiful energy storage (mostly in the form of utility-scale electrochemical batteries) is the resource we need to (build and then) steward for grid resilience.

The Consequences of Poor Stewardship Come Later

The grid is part of the engineered infrastructure that underlies our way of life and economy. Other parts include roads, airports, railways, bridges, broadband cables, water pipes, levees, waste treatment plants, and school buildings. Infrastructure stewardship is an investment of labor and capital in future ease. Which suggests that some of the hardship that (usually less wealthy) members of our society experience now can be attributed to inadequate infrastructure stewardship in the past. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gives the U.S. infrastructure a C- overall. To enjoy the infrastructure we want now, we would have had to invest in infrastructure resilience years and decades ago.

Stewardship: pay now, share benefits later — the opposite of the proposition offered by temptation, which is short-sighted and selfish.

Stewarding Mental Health

On the subject of personal hardship, a good deal of individual suffering can be attributed to a failure of mental health stewardship. The Mayo Clinic and the American Psychological Association have a few tips that won’t surprise anyone, paraphrased here:

Exercise, sleep, and eat properly.

Connect with others through spiritual or faith groups.

Be of service in others’ efforts to connect.

Reflect and discuss successes and failures to learn from them.

Figure out what help you need and ask for it.

These are principles. The specifics of execution — the how-tos — vary from person to person, as it should be.

Principles cannot reasonably be expected to work overnight — whatever blossoms will appear in due time. The good news is principles are mutually reinforcing; the other news is that one at a time may not be enough.

A Stewardship Summary

System resilience emerges from stewardship of at least one key underlying resource. The best way to steward a given resource may vary with context and personal preferences — more on this in Part 2.

For now, here are the key characteristics of stewardship as I see them:

Invest in shared resources now, share benefits later.

Benefits accrue gradually over time.

Benefits tend to be mutually reinforcing.

There is a short-term benefit: It is work that feels good.

Stewardship specifics may vary with context, but the principles are universal.

For a given resource in a given context, there might be more than one right answer to the question of how best to steward it.