The U.S. Illiteracy Spiral

“Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope. It is a tool for daily life in modern society… Literacy is, finally, the road to human progress and the means through which every man, woman and child can realize his or her full potential.”

~Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations

Calvin’s Story

When my stepson, who I will call Calvin, was in fourth grade, he was tested as reading at a second-grade level. There were hints that he was beginning to think of himself as dumb. But his curiosity and ability to string ideas together made it clear to us he was plenty smart.

His mom took him to a specialist to get tested, then found a private tutor to help him get past the reading hump encountered by dyslexics early on. By the end of seventh grade, Calvin’s reading results were college-level.

I believe that was a life-changing fork in the road for Calvin. It changed the way he talked about himself. It opened his world to new possibilities. He will have options he would never have had without professional help delivered early in life.

Reading is still a problem with Calvin, but it’s the reading problem we want: Left to his own devices, that kid would stop reading only to sleep or (maybe) eat a meal. We sometimes have to pause him.

But here’s the thing. We had access to a tutor and the financial resources to pay her. That is not true for many dyslexics in the U.S. A Calvin clone with less luck in the parental finance department would be headed down a different life path.

Dyslexia

According to The Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, dyslexia affects about 20% of the U.S. population, or 66 million people of all ages, genders, ethnicities, cultures, IQs, and EQs. Untreated, says the Mayo Clinic, dyslexia can lead to low self-esteem, behavior problems, anxiety, aggression, and withdrawal.

Austin Learning Solutions claims that only about 5% of dyslexics know they have it, which I will take to mean 95% of dyslexics are untreated. Therefore, about 63 million people in the U.S. may struggle with low self-esteem, behavior problems, anxiety, aggression, and withdrawal simply because they have an untreated, but treatable, no-fault condition. (I wonder how many tragic news stories in the U.S. today could have been avoided by treating some kid’s dyslexia twenty years ago.)

Dyslexia is not the only learning “disability” with a bad influence on literacy rates, either. And what about the U.S. literacy rate? For one thing, it is low compared to other wealthy countries (more on this in a later post). Economists are clear: a nation’s literacy rate is a strong predictor of economic growth. So…a low U.S. literacy rate…not good.

But in this post, we are looking at the microeconomic link between literacy and income.

U.S. Literacy — How Bad Is It?

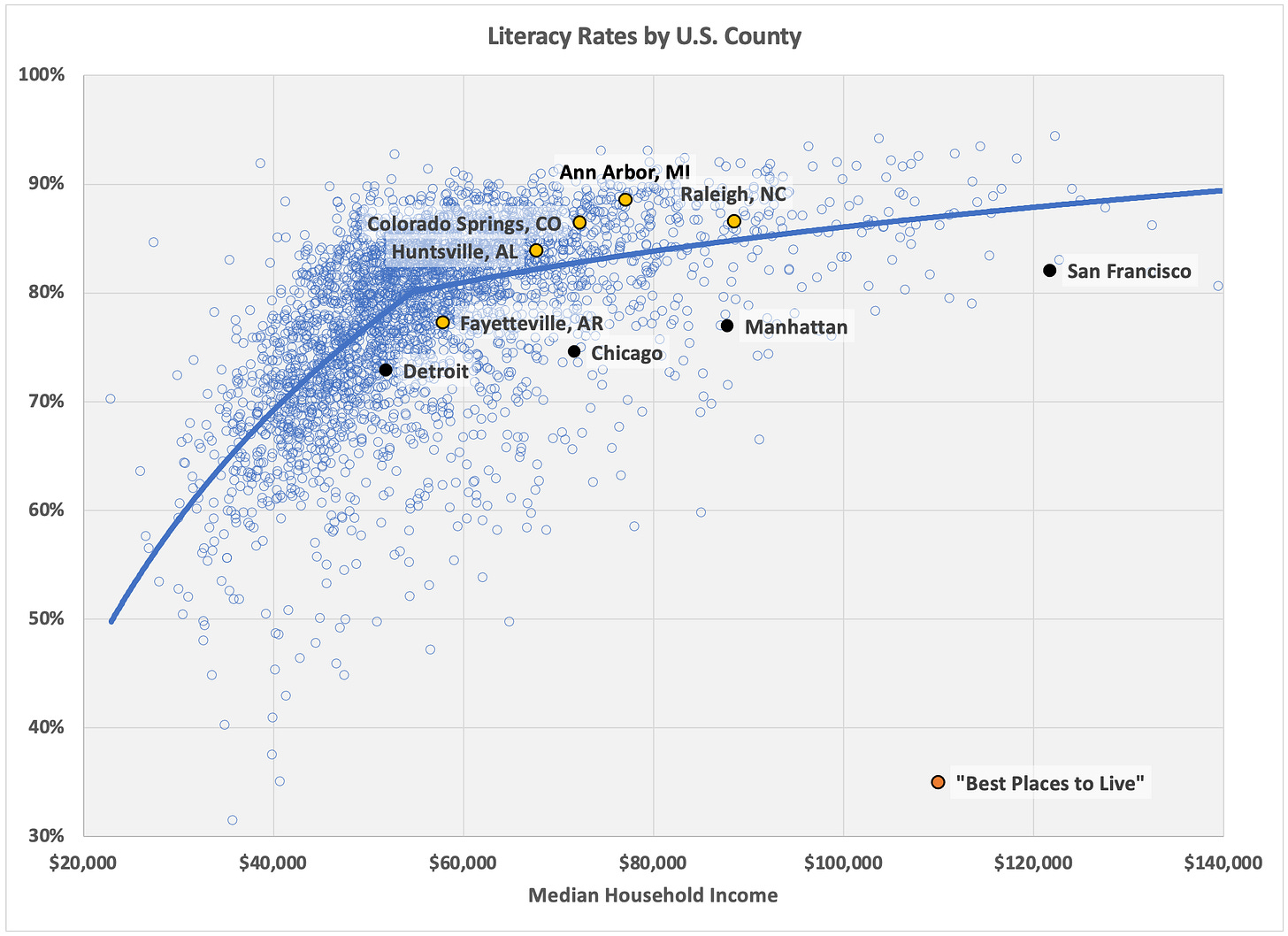

For every county in the U.S., the above graph shows the average literacy rate versus the median household income. There are two trendlines, one for the bottom half of the income scale, the other for the top half. I did it this way because a single unbroken trendline doesn’t follow the main mass of the dot cloud well. The trendlines are best logarithmic fits, in alignment with the way economists usually view income. A logarithmic fit depicts how literacy changes given a percentage change in income, whereas a straight line would show how literacy changes given a dollar change. The counties containing four big U.S. cities are shown for context. The yellow dots are counties containing one website’s take on the five “best cities to live in.” (It is probably no coincidence that four of the five are clustered at high literacy rates and above-average incomes.)

Literacy rates in this newsletter are based on results from an international standard, administered by the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). In the U.S., the total number of participants was about twelve thousand, a relatively small dataset that did not cover all counties. Based on these results, the researchers built a probabilistic model that predicts literacy given other data available from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), which does cover all counties. Their model then allows them to predict literacy for counties outside the PIAAC study area.

The PIAAC test results are aggregated into five levels. People at or below Level 1 are “…considered at risk for difficulties using or comprehending print material.” In this newsletter, Level 2 or better on the PIAAC test indicates “literacy.”

Level 2 corresponds to a sixth grade reading level — “literate” but not proficient. Over half of adults in the U.S. read at Level 2 or below. I wonder what percent of the information available in our world is a) nuanced and thoughtfully written, and b) written at a sixth-grade reading level. Pure speculation here: I bet one of the reasons we have so much angry discourse marked by false claims of either/or, this/that, black/white in our national conversation is that most of us are not equipped to read and understand nuanced writing.

We established a democracy, sort of, and then miseducated most of our voters! Seems unwise. Anyway, back to the micro view…

A Causal Loop

The graph shows a clear correlation between literacy and income, but says nothing about which causes the other. As is often the case with inequity issues, it is easy to make a case that literacy and income reinforce each other. Low income makes it hard to get help outside the school system for kids who learn differently. The help required is often not inside the school system because of budgetary restrictions on hiring and teacher training.

In the U.S., most school budgets are dictated by the size of the local property tax base. So, to the degree that education quality is influenced by the size of school budgets, literacy rates are influenced by the wealth of local families. Higher childhood literacy leads to higher income and wealth in adulthood. Then the children of those adults get better educations. ‘Round and ‘round goes the causal loop. (If we were trying to worsen education inequity without breaking civil rights laws, I don’t think we would do things much differently.)

Bottom line: Circumstances of birth influence literacy, which makes literacy an equity issue. Since income influences — and is influenced by — the circumstances, income correlates with literacy.

Next up: Why life expectancy and infant mortality are equity issues correlated with income.