This and no other is the root from which a tyrant springs: when he first appears he is a protector. ~Plato

That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach. ~Aldous Huxley

Fair warning: This is a long one compared to my usual.

Economic problems don’t have to be super catastrophic to cause real suffering for a large portion of the population. For example, the gold standard caused suffering for at least a century, continuing even after the U.S. dropped it for good in 1971. At the same time, and until recently, macroeconomists’ poor understanding of macroeconomics made it worse.

Presidents and externalities (like wars and pandemics) get the blame for economic problems. But really they are just excuses. Externalities happen; the question is whether we are responsibly prepared for and resilient to the unforeseen. As for politicians, realistically they can only be relied upon to do what gets them (re)elected. All too often, short-sightedness is rewarded by votes but hurts our economy twenty years down the road.

The Fed’s job — maintaining healthy growth, balanced between high unemployment and high inflation — is a short-term one. As with all balancing acts, it requires immediate dynamic action so the economy doesn’t fall out of balance, which has longer-term consequences.

So who’s minding the medium- to long-term economy? In an ideal world, politicians, who enact fiscal policy, would be far-sighted. They would be far-sighted because a) voters would be far-sighted and thoughtful, and b) voters’ voices would not be drowned out by big-money-funded election campaigns. Meanwhile, the Fed would be quick on the uptake to avert longer-term problems.

But we have this world. So we have had unnecessary economic volatility and increasing inequity, which has hurt long-term growth. We are seeing hints of improvement on both fronts, so that’s hopeful.

Mostly, though, U.S. economic history has been a story of monetary policy errors exacerbated by short-sighted fiscal policy. That short-sightedness has often been triggered by the lingering social consequences of…previous bad monetary policy.

The Gold Standard Is Fundamentally Unworkable in a Modern Economy

The gold standard might be fine for a simple barter economy in which people trade across space. But since we also trade across time, we need lenders and borrowers. So we need banks. Banks’ lending rates determine which projects investors are willing to take on. The projects’ payoffs drive economic growth. Thus, low lending rates accelerate growth.

Not coincidentally, low lending rates cause and are caused by more money in circulation. Supply-demand interactions dictate that increases in money supply result in lower prices for money (interest rates). Unfettered, then, rates would spiral down and growth would accelerate unsustainably.

But there are natural limits to too much lending: 1) the threat of bank runs and 2) high wages caused by low unemployment caused by an overabundance of loan-funded projects. In today’s U.S. economy, there is also a regulatory limit to banks’ loan-to-deposit ratio. But none of these limits are dynamic enough to deal with the externalities that jostle an economy.

The gold standard shares the same problem as the natural limits mentioned above — it’s not dynamically responsive to externalities. Plus, it is more restrictive on the money supply than the other limits and worsens the bank run threat. So in the absence of a central bank that can increase the money supply by lending to commercial banks (so they, in turn, can lend more and also fend off bank runs), the gold standard stifles investment. What stifles investment stifles growth and employment.

So we need a central bank, which we got in 1913. But that left us with a gold standard and a central bank. That meant the money supply became what an engineer might call over-specified. Sooner or later, something was going to break.

Gold Standards Contributed to the Great Depression and Other Bad Things

First of all, it’s not really “the” gold standard. We have tried a few variations and they all caused or contributed to economic problems, then broke.

In 1834, the U.S. pegged the value of a dollar to $20.67 per ounce of gold. We adhered to that price for 99 years, until 1933. The “Classical Gold Standard” was formalized for the U.S. in 1900 by the Gold Standard Act. By then, problems caused by the overly restrictive nature of a gold standard were already in play on the global stage, and then came to a head when World War I broke out in 1914. Nations’ financial markets were destabilized and could not support the fixed exchange rates inherent in an international gold standard. To avoid collapse, warring countries — including the U.S. when we entered the war in 1917 — suspended strict adherence to the gold standard in various ways. (Break #1)

In 1919, the U.S. recommitted to an international gold standard. Over the following eight years, other major countries followed suit, establishing the “Gold Exchange Standard.” In this version, countries other than the U.S. and Britain held reserves in gold, dollars, or British pounds. The U.S. and Britain could hold only gold and our exchange rates with other countries were fixed.

During the Great Depression, the U.S. needed to expand our money supply in order to lower rates and invigorate growth. But the gold standard, by its nature, restricted the money supply, so in 1933 under FDR, we dropped out of the Gold Exchange Standard. Not, however, before it had worsened the Great Depression by restricting the Fed’s ability to lend to commercial banks threatened by bank runs. (Break #2)

The U.S. central bank, the Fed, was in place by this time, but that doesn’t mean economists understood macroeconomics very well. We switched to another version of the gold standard, the “Quasi-Gold Standard” in 1934. In this one, U.S. citizens were barred from owning gold while international trade was conducted using fixed exchange rates. At the same time, the value of a dollar was changed drastically to $35 per ounce of gold. This would have amounted to sudden and catastrophic deflation. But U.S. citizens, following mandatory sales of their gold to the government at the $20.67 price, were not allowed to exchange gold and dollars. So overnight, the price of gold became domestically irrelevant, at least in the short term.

But gold standards were “known” to stabilize economies by stabilizing the money supply, so we kept trying. The Quasi-Gold Standard was further formalized with the Bretton Woods international agreement, drafted in 1944 and launched in 1958.

Then in 1945, the Great Depression and World War II both ended. A lot happened next. War bonds matured, increasing consumers’ income and contributing to a release of pent-up demand. The GI Bill helped educate the workforce and empower investments in their homes. Returning GIs flooded the labor market, increasing the unemployment rate, but strong unions helped keep wages relatively high. The baby boom and a highway infrastructure build-out further stimulated the housing boom. Highways and highway construction provided jobs, increased overall productivity, and paved the way for suburbs. Productivity was spurred by the industrialization of agriculture. Airplane manufacturing and air transportation grew exponentially, also contributing to growth.

President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ), who held office from 1963 when JFK was assassinated until 1969, had an outsized (even for a president) influence on U.S. socio-economic events. In a recent tribute to LBJ and President Joe Biden, comedian Marjorie Taylor Greene, who until recently had never publicly dropped her stage persona as a hyperbolic MAGA moron, stepped briefly out of character to mention LBJ’s legacy vis-à-vis “Bidenomics”. LBJ presided over two historic events: 1) his Great Society policies — the “war on poverty” and a fight against racial injustice — and 2) escalation of an actual war, the one in Vietnam. The wars competed for funding and obviously had opposite effects on aggregate well-being.

The upshots of the socio-economic upheaval of the 1950s, ‘60s, and early ‘70s were drastic improvements in income inequality (overall, but less so for minorities) and volatile economic growth. There were post-war slumps in 1945 and 1953. A recession in 1949 was brought on by a drop-off in the post-war release of pent-up demand combined with high interest rates. The 1958 recession was triggered by a pandemic and compounded by high interest rates. The 1960 recession is blamed primarily on inappropriately high rates.

Clearly, monetary policy was not mitigating the impacts of macroeconomic externalities during this era. At the time, the Fed raised rates in response to rising inflation, but generally kept rates low to “promote maximum employment,” as called for in the Employment Act of 1946. Unemployment during this period was kept too low, which placed upward pressure on inflation, which then led the Fed to raise rates. High rates contributed to or outright caused recessions. Rates were turned back down too soon and/or too low, which set the stage again for rising inflation. In short, the Fed was part of the volatility problem.

With rates too low on average throughout the 1960s, inflation continued to grow. The Fed’s response was slow and anemic, but inflation topped out briefly in 1966. Then in 1967, the Fed bowed to political pressure and lowered rates much too soon. Predictably (we would say now), inflation rose again, which finally prompted a more aggressive raise in rates. But the die had already been cast for the next recession in 1970, this one entirely due to bad monetary policy — economists at that time still didn’t understand how unemployment needed to be balanced against inflation. By the end of the 1970 recession, inflation was high and unemployment was rising precipitously.

Meanwhile, the fundamental unworkability of the Quasi-Gold Standard under Bretton Woods still lingered. The bouts of U.S. inflation motivated other countries’ central banks to hold dollars instead of exchanging them for gold. They believed that the fixed amount of gold a U.S. dollar would buy was becoming increasingly and unrealistically low. By the mid-1960s, foreign central banks held more U.S. dollars than the U.S. had in gold reserves.

Bretton Woods had mitigated U.S. bank runs by effectively eliminating the gold standard within U.S. borders, making way for the Fed to manage the domestic money supply. But the bank run problem had not been eliminated; rather, it was rearranged and magnified: The threat of a run on gold posed by other countries was a bank run writ large, with the Fed as the bank in question.

No doubt motivated by political expediency, President Nixon needed a short-term solution and probably (understandably) felt he could not rely on the Fed. In 1971, he unilaterally withdrew from Bretton Woods to avoid a gold run and instituted price and wage limits to try dealing with domestic inflation. The withdrawal worked; the limits did not, at least in part because they were instituted in exchange for the Fed lowering rates prematurely. That political compromise by the Fed helped kick off the Great Inflation era. (Break #3)

Finally, though, after well over a century and failures of every version we tried, we were rid of the gold standard, a fundamentally flawed monetary strategy. Unfortunately, during and immediately after the gold standard strategy, we also practiced poor monetary tactics. The Great Inflation, the “greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the postwar period” was then under weigh.

Externalities — wars, pandemics, trade embargoes, industrialization, unequal growth rates among trading partners, short-sighted political maneuvering, etc. — would have happened without bad monetary strategy and tactics. They would have jostled our economy about and caused some recessions even with good monetary policy. Instead, our monetary policy was consistently poor. During the 1970s, the U.S. economy veered off the rails.

The Great Inflation

Even good monetary policy doesn’t prevent externalities. In 1973, OPEC’s oil embargo triggered a spike in inflation and another recession. During our recovery from the ‘73 recession, a combination of high rising inflation and low unemployment should have spurred the Fed to raise rates aggressively. This was especially true given the self-fulfilling expectations of more high inflation due to low confidence in the Fed.

Alas, instead of an aggressive raise, the Fed raised rates cautiously. Consequently, high inflation was insufficiently mitigated, blasting through 10% on its way to almost 15% in 1980. During that time, another difficult externality occurred: the Iranian revolution brought on a second energy crisis in 1979. Responding to the oil crisis amid bad monetary policy, growth took a downturn. In 1980, we found ourselves in yet another recession.

The runaway inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s is often blamed on President Carter’s policies. In fact, it was caused by bad monetary policy before he entered office. As a result, our economy was especially vulnerable to externalities like the oil embargo.

The popular story about “stagflation” holds that President Reagan defeated inflation with deregulation and tax cuts. Not true. As Noah Smith points out, “Carter was a deregulator who didn’t increase deficits much, and appointed [Volcker,] who beat inflation. Reagan didn’t do much deregulating...” What he did do was cut taxes for the wealthy and reduce funding for social programs.

Carter’s deregulation in the ‘70s, followed by Reagan’s tax cuts and defunding of social programs in the ‘80s, are examples of short-sighted fiscal and social policies triggered by economic hardship that really should be blamed on previous poor monetary policy. Monetary policy sets the stage; political expediency in the form of fiscal and social policy follows. Expediency implies short-sighted, and short-sighted usually entails unintended longer-term consequences. Deregulation, tax cuts for the wealthy, and defunding of social programs all contributed to increasing income inequality over the subsequent forty years. High income inequality hurt growth.

In what may have been one of the best economic policy decisions in U.S. history, Carter appointed Paul Volcker as Fed Chairman in 1979. Volcker had some ideas about the importance of managing inflation expectations. He inherited a huge economic mess — skyrocketing inflation and a Federal funds rate already at 10%. As with all things macro, economic inertia guaranteed that even if he immediately instituted decisive and appropriate policy, things would get worse before they got better. Meanwhile, nobody really knew if his ideas would work…

The Great Moderation

Believing that inflation expectations were key to managing inflation, Volcker committed publicly to predictable rates in response to inflation data. This earned the Fed some credibility, which calmed inflation expectations and eventually brought inflation back down. But it came at the cost of a recession — the economy was too far out of whack at that point to reasonably expect otherwise.

Under Volcker, who held the Fed Chairmanship until 1987, and then Alan Greenspan, who held it until the end of 2006, the economy recovered and stabilized, demonstrating much lower volatility. Between 1983 and late 2007, there were only two recessions. The 1990 recession was brought on by a combination of the savings and loan crisis, which we can blame on financial deregulation, and a spike in the price of oil resulting from the Gulf War. The 2001 recession was another one-two punch: The Dot-Com Crash and 9/11.

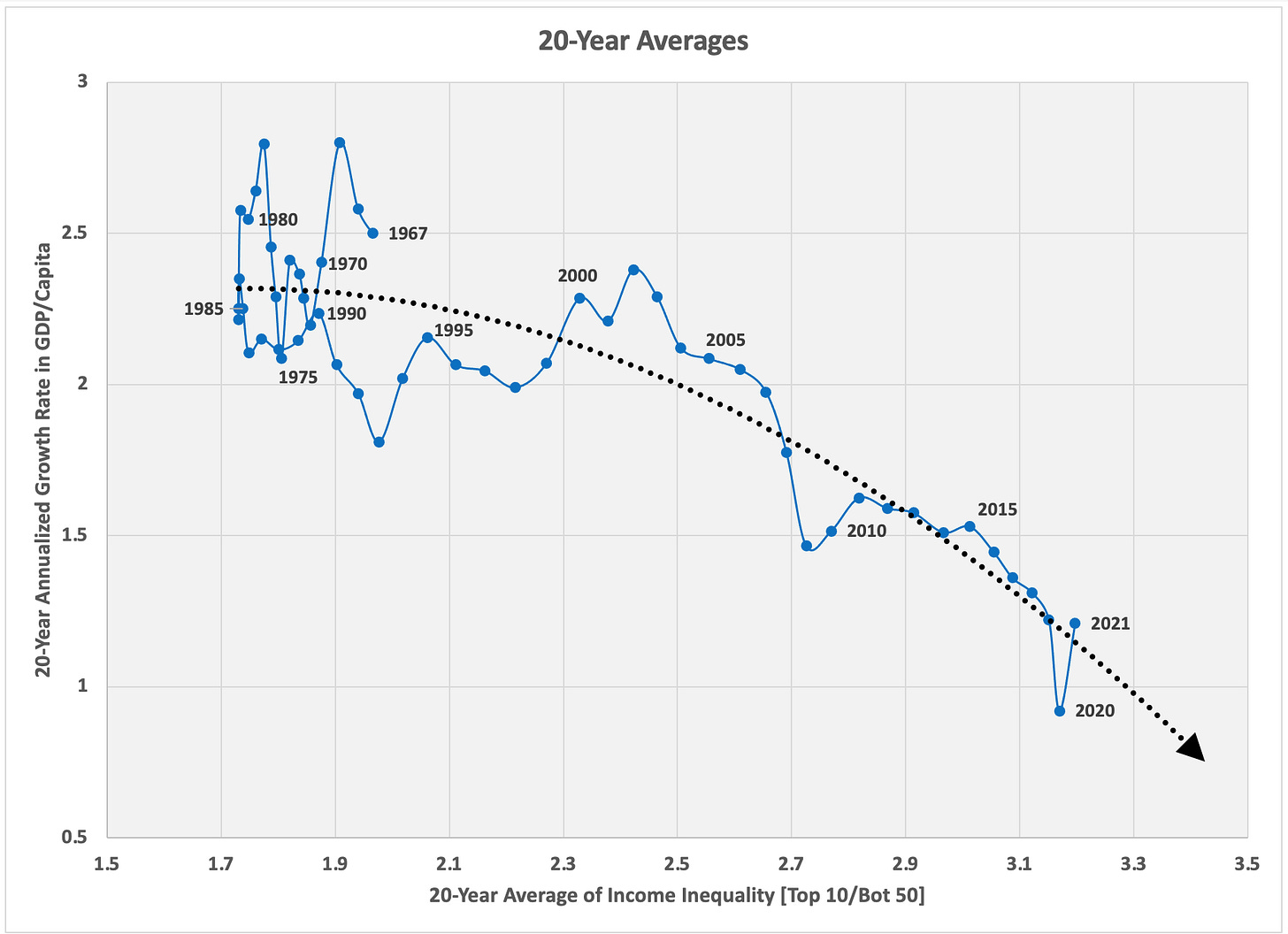

But…behind the scenes, as illustrated in the graph at the top (which first appeared here), income inequality was skyrocketing and long-term economic growth was drooping. Furthermore, financial deregulation had not yet done its worst.

The Great Recession and Slow Recovery

The Great Recession was also caused by poor financial regulation. The housing bubble was the proximate cause, but the housing market was just a vehicle for predatory financial institutions. As with all bubbles, the housing bubble eventually burst, wreaking more havoc than most bursting bubbles because “…housing forms the backbone of middle class wealth, and the middle class is much more likely [than the wealthy] to cut back on consumption when their wealth falls.”

By the end of 2008, in response to high unemployment, the Fed had lowered their policy rate to zero, the lowest it can realistically go. Why was unemployment the problem this time and not inflation? In the lingo I use in Part 1, housing is a type of project. A burst housing bubble amounted to a cutback on projects, and thus a cutback on jobs. Unemployment increased. Thus spending (aggregate demand) decreased, so inflation remained low and even decreased.

The Fed was 6-12 months late in its response to the burst housing bubble in 2007, especially in the context of a drastic rise in oil prices from 2004-2008. Worse, because growth and therefore long-term average inflation had drooped over the previous 30 years, the interest rate necessary to support balanced growth had drooped. Given the severity of the burst housing bubble, there was not enough room to lower the rate by as much as the Fed would have liked. Too little reduction, executed too late. We needed a Plan B.

The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 (tax rebates, business tax incentives, and less restrictive limits on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgages), signed by President George W. Bush, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 (tax incentives, aid for healthcare and education, boosts in unemployment and poverty spending, and infrastructure spending), signed by President Barack Obama, were intended to stimulate growth. They were not enough, however. Paul Krugman asserted recently that with more of the right government spending, we could have recovered by 2011.

Meanwhile, the Fed tried something new: quantitative easing (QE). They engaged in three rounds — 2008, 2010, and 2012 — trying to speed up our economic recovery. QE is believed to have helped (and here) but we did not return to balanced inflation and unemployment until 2016. By that time, inequality had risen nearly to Great Depression-era levels while long-term growth had dropped below 2%.

The Pandemic and Trump

Very high income inequality makes people angry. In 2015, angry people elected a president who looked as if he might upend the system many of us blamed for our discomfort. Exasperated voters tossed a hyper-narcissistic stick of dynamite into the White House.

One of the lasting impacts of the Trump administration has been that enough right-leaning judges were appointed to change the dominant ideology of the U.S. Supreme Court and some of the thirteen federal appeals courts. The problem is that “right-leaning” at the judicial level tends to bring on less-inclusive laws over time. (And sometimes suddenly.) Pretty much by definition, less inclusivity leads to less equity.

Trump also reinforced science denial in the face of the Covid-19 Pandemic and climate change. The Pandemic and climate-related disasters disproportionately impact the poor, worsening inequity. There was the whole business of The Wall, which was compassionless policy executed poorly, contributing to a great deal of suffering for some human beings already severely disenfranchised. He cut taxes for the wealthy again, and to be clear, at this point in our national economic journey, economists know that’s a bad idea. He also rolled back some of the financial regulation that came in response to the Great Recession.

In any case, I see Trump as a symptom of a much bigger problem (see opening quotes). As conservative NYT opinion writer David Brooks asks, “[W]hen will we stop behaving in ways that make Trumpism inevitable[?]” My answer: When we embrace social equity as a key economic indicator.

When the Covid pandemic hit, low long-term growth left the Fed with little room to lower interest rates. More room would have helped, but to be fair, another point or two in growth and interest rates would not have prevented smashing into the policy rate’s zero lower bound (ZLB). As in the Great Recession, our encounter with the ZLB necessitated QE, which the Fed enacted in March of 2020.

And again, we needed aggressive fiscal policy in parallel. This time we got it. In 2020, Trump signed off on the CARES Act and in 2021, President Biden enacted the American Rescue Plan. These policies were wide-ranging in their effect, pouring money into expanded unemployment coverage, child tax credits and child care, health insurance, national paid leave, improved food assistance, eviction prevention, and aid to state, local, and tribal governments.

It was “helicopter money” raining down from the sky; some of it was bound to be poorly targeted. But the Brookings Institution gave the American Rescue Plan a good review. Most of that money found its way into the right hands, as illustrated in Timothy B. Lee’s Full Stack Economics newsletter:

The massive influx of money into general circulation probably saved us from a much worse economic fate. But the flood of money lingered and has had lasting effects, to which the Fed was again slow to respond.

Post-Pandemic Recovery

The lingering money injected by two administrations plus the year-late (my opinion, based on my PhD research) interest rate hike by the Fed caused a huge spike in inflation. Now that they’re on it, though, it seems like the Fed is cleaning up the mess about as well as could be expected.

Their efforts have been greatly helped by Biden’s “industrial policy,” which is fiscal policy aimed at reducing our dependence on foreign (especially Chinese) trade, spurring economic growth through infrastructure investments, and investing in climate change solutions. Current industrial policy has mostly taken the forms of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act.

To my eyes, it looks like inflation and growth are recovering nicely due to (late but now appropriately) aggressive monetary policy while unemployment has been kept low with help from aggressive spending on industrial policy.

In more good news, there are hints that inequality might be on the mend, at least for now. This is consistent with what we know about the effects of social policy spending, which, in response to the Pandemic, we did more of than usual. The question is, what will happen to income and wealth inequality (and social inequity) as Pandemic-inspired social spending peters out?

Summary

Monetary policy operates in the short-term but matters a great deal in the medium- and long-term for two broad reasons:

As with any balancing system, deviations now from perfect balance inform the dynamics we’re about to get.

When the economy does fall out of balance, undesirable dynamics include volatility, high unemployment, and/or high inflation. All of these outcomes lead to short-term thinking — political expediency — which often results in fiscal/social policy imposing negative unintended consequences in the longer-term.

Looking through the lens of U.S. monetary policy history, our current socio-economic woes — social division and an inflation spike — can be seen as results of a series of socio-political reactions to decades of bad monetary policy. In this post, I cast my glance only as far back as World War I, but one could — and many have (Capitalism and Slavery, The Half Has Never Been Told, The Color of Law) — trace current socio-economic problems to the short-sighted economics of slavery.

The changes we need, I think, amount to shifts in our culture:

Encourage the Fed to be a notch more dynamic in their decision-making and execution. For this, we would need to be at peace with more volatility in short-term rates to maintain smoother long-term balance. We would need to hold on a bit more loosely, as it were, so we don’t lose control in the longer-term.

Incorporate into our national awareness the idea that inequity, although tempting in the short-term, hurts growth in the not-too-distant future. Maybe we could be more thoughtful — even compassionate — in crafting fiscal policy and financial regulation.

Next up: Now what?