Brilliant theorists of economics do not find it worthwhile to spend time discussing issues of poverty and hunger. They believe that these will be resolved when general economic prosperity increases. These economists spend all their talents detailing the processes of development and prosperity…As a result, poverty continues.

~Muhammad Yunus, economist and Nobel Peace Prize winner

What’s Monetary Policy Got To Do With Equity?

I have written that monetary policy is silent on income inequality. The only goal of monetary policy is to maintain balanced economic growth. “Balanced” because high growth is associated with high inflation and low growth is associated with high unemployment.

Good monetary policy resulting in balanced growth does not directly mitigate inequity’s tendency to get worse. But bad monetary policy, if it causes growth to get out of whack, can lead to a misguided weakening of social policy…which eventually hurts growth even more. That is why monetary policy matters to equity.

So good monetary policy contributes to short-term economic health by balancing growth; it contributes to medium- and long-term economic health via its indirect influence on equity. But from what I can tell by reading the news, monetary policy and macroeconomic dynamics are not widely well understood.

This post lays out my understanding of macro informed by my economics PhD research and filtered through my — for better or worse — engineer’s mind. In the next post, Part 2, I will compare what we have done over the last eighty years to what we probably should have done based on this understanding.

1) The Fed

Effectively, the Fed sets the short-term interest rates charged to commercial banks. (They also engage in quantitative easing, which I will get to below.) This “policy rate” is the basis for the rates we are familiar with in day-to-day life, charged to us by commercial banks and other financial institutions.

When short-term rates increase, expectations about future short-term rates usually also increase. But “expectations about future short-term rates” is just another way of saying long-term rates. For example, a 5-year interest rate is our best guess for how all the short-term rates between now and five years down the road will stack up. If we expect future short-term rates to settle down, the corresponding 5-year rate will be lower than if we expect short-term rates to stay high.

When long-term (or medium-term to be consistent with language in a previous post) rates go up, it discourages investments in long-term projects like corporate capital investments and residential real estate. For a project investment to make sense, one would need to expect the project’s payoff to outpace the long-term interest rate being charged by the lending institution from which the investment money would be borrowed.

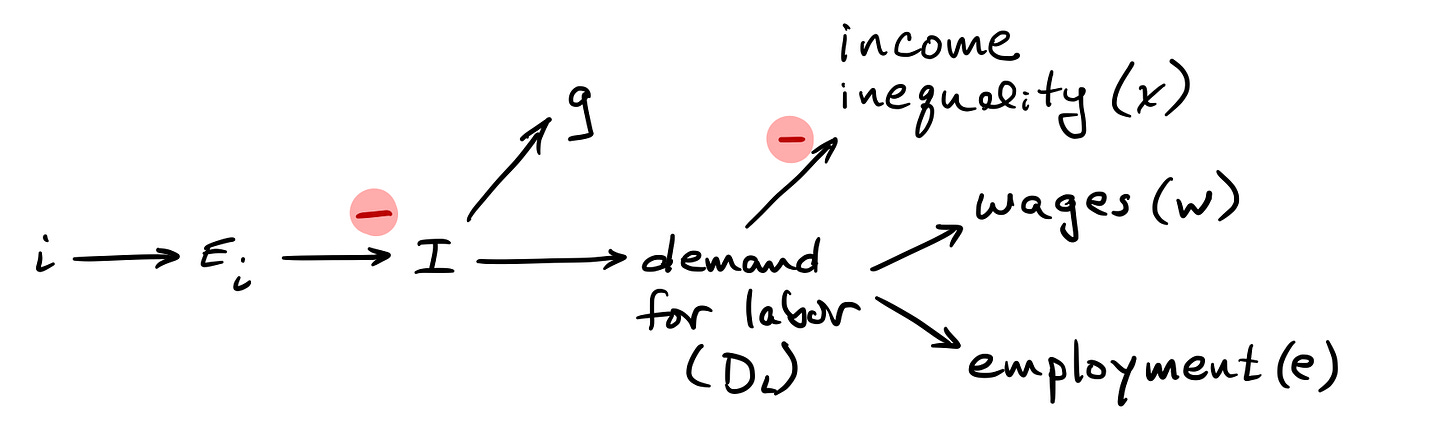

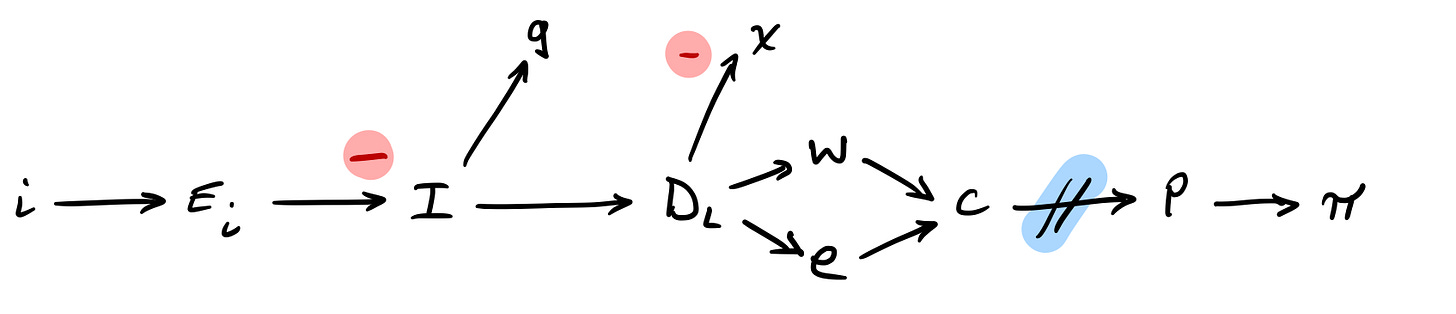

The causal diagram above summarizes this. The red minus sign means a change in direction: higher interest expectations lead to lower levels of investment; lower expectations lead to increased investment. No red minus sign means no change in direction. For example, more investment leads to more growth and less to less.

2) Labor

Projects need workers, so if investment increases, labor demand increases. Wages and employment levels follow. As discussed in this post, increased (decreased) demands for labor result in temporary decreases (increases) in income inequality. Temporary because there are a host of other factors in the medium- to long-term that also influence income inequality. More on this below.

3) Prices

Better employment and higher wages lead to more consumption, which eventually leads to increased prices. Economists say prices are “sticky” or “rigid.” Both mechanical metaphors are poor. It’s more like spring-and-damper behavior, with prices increasing smoothly over a period of about six months in response to a jump in consumption.

The most plausible reason, in my opinion, for sluggish price movements is risk management. Changing prices in a competitive market is risky, so businesses tend to avoid sudden moves in this regard. Managers may engage in analysis, which takes time, and also avoid being the first among their competitors to make a change. As a result, in aggregate, there is a delay, indicated in the diagram with double slashes.

As for inflation and deflation, they are defined as changes in aggregate prices.

4) Set and Forget?

This diagram summarizes how the Fed’s interest rate filters through the economy. Since we don’t want low employment, there is an incentive for higher interest rates. But since we don’t want high inflation, there is an incentive for lower interest rates.

So why not set the interest rate at its Goldilocks value (around 2% given the Fed’s 2% inflation target) and be done? If interest rates were steady, according to this diagram, investment rates would be steady, as would growth, income inequality, employment, and inflation. That is obviously not the case, so what’s missing?

In a word, externalities.

5) Externalities

Confidence in the economy — and confidence in the Fed’s ability to get us back to economic health from economic deviations — spurs investment. Note that our confidence in the Fed can work against us! In recovering from a recession, it helps: The Fed lowers rates, spurring investment and growth, in sync with economic confidence arising from Fed credibility.

But in a situation as we have now — high post-Pandemic inflation — the Fed raises rates to damp inflation. If we believe it will work, our confidence remains high, which tends to keep investment high, working against the Fed’s main tool, the short-term interest rate. This probably explains, at least in part, the “stubbornness” of inflation right now.

Regarding income inequality, as discussed in some detail here, there are several factors at play. The Fed’s influence on income inequality is short-term, whereas the factors shown as externalities in the diagram are medium- and long-term. Furthermore, the Fed has only one control lever (or two if you count quantitative easing as a separate lever) and two responsibilities — inflation and unemployment. Adding income inequality, given its relationship with the other two, as a third responsibility would not be realistic.

Also subject to externalities, prices can be jostled around by many factors, some of which are shown in the diagram.

When the economy gets knocked out of balance by externalities, as it does, the Fed moves its short-term interest rate to get us back on track. Because inflation and employment work against one another, and because time lags exacerbate the recovery dynamics, the Fed’s balancing job is far from “set and forget.”

6) Two Balancing Acts

Usually, the Fed’s interest rate-setting behavior is modeled as a reaction to inflation and unemployment data since those are their key performance metrics. (Data is noisy and delayed, so they monitor other things, too, like consumer confidence, growth itself, financial market performance, foreign exchange rates, etc.) But essentially, rising inflation applies pressure on the Fed to raise their interest rate; rising unemployment (decreasing employment in the diagrams) applies pressure to lower the rate.

Because of system delays, the Fed would like to act early. Because the data is noisy and because the science of economics still has some art to it, they would also like to be cautious. So they are left with another sort of balancing act on top of their charter to balance inflation and unemployment.

7) Quantitative Easing

One last bit in what has become a somewhat complex picture (sorry): quantitative easing (QE).

The actual mechanics of setting the short-term rate involves the Fed buying and selling short-term financial assets on the open market. When they buy assets, the supply of money in general circulation increases, lowering the price of short-term money a.k.a. the short-term interest rate.

In quantitative easing, the Fed buys longer-term assets, which raises the prices of those assets. (It also increases the money supply, but that is not the main point of QE.) Raising the price of long-term assets is equivalent to lowering aggregate expectations for future short-term interest rates (Ei in the diagram). [For such a short sentence, that one might be hard to digest.] Here’s an example: If you want to pay somebody now to obligate them to pay you $100 in five years, the amount you would pay them depends on the 5-year interest rate you agree on. The lower your 5-year rate, the more (the prospect of) that future $100 is worth today, so its price is higher. A higher price for a long-term asset = a lower long-term interest rate.

Why use QE? The main reason so far has been that the Fed wanted to lower the short-term interest rate more than it could because it ran into a hard stop at 0%. It happened in the Great Recession of 2008 and the Pandemic recession.

OK, but why are we running into the 0% hard stop now but not historically? Partly because growth that qualifies as “balanced” has drooped over the past forty years. Therefore, the level of inflation and short-term interest rates that qualify as balanced have also drooped, bringing the average short-term interest rate closer and closer to zero, making a hard stop more likely.

Well, why is growth drooping, then? This is debated among economists which almost certainly means there is more than one reason, but I strongly suggest rising inequity as one of them.

Next up: Part 2, in which we look at how monetary policy (good and bad) has impacted our economy (directly and indirectly) over that last eighty years.